The Failings of the AIGA

Written by Erin Malone

AIGA, which was formerly called the American Institute of Graphic Arts, started in 1914 as a community of practice and professional organization for those involved in the graphic arts. The group was made up of men working as typesetters, type designers, printers, and production managers; women were not allowed membership until 1920. As advertising and corporations created internal creative teams, more graphic designers and art directors joined during the mid-century explosion of design, and the production side of the membership diminished.

The first woman was not elected president of the group until 1958. Over its 100 plus year history, only six women have been elected president of the organization, despite the increasing numbers of women in the field of design. In 2005, the organization dropped the full name and went with the acronym to be known as the professional organization for design. In the late 90s AIGA, with the Advance for Design initiative and then the Experience Design SIG, attempted to become the home for this emergent type of designer—user experience designers. Most members were graphic designers turned digital designers. But the fit was off. The focus of the organization was still primarily graphic design, manifested through print design. This can be seen in the AIGA annuals of the time which showed very little inclusion of digital work.[1]

Digital user experience designers found new homes that were more relevant and focused to their specific flavor of design with its relationship to behavior and technology as UPA evolved, the IA Institute was founded, and IXDA was born. By the 2010s, the Experience Design SIG was no longer called out on the website and archives from the Advance group and the DUX conferences with CHI, were no longer available. There is currently a section of the website called Experience Design but it only links to a handful of more recent articles.

In the late 2010s and into the 2020s, AIGA has also been called out as being hostile to Black designers of all disciplines. In 1991, the AIGA was the original host of a symposium “Why is graphic design 93% white?” The symposium was inspired by Cheryl D. Miller’s 1987 Print magazine piece, “Black Designers: Missing in Action,” which put the design world on notice. By 2016, the organization developed multiple sets of initiatives to increase diversity. Black designer, social entrepreneur and diversity, equity and inclusion specialist, Antoinette Carroll was named the Founding Chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Task Force. She was formerly an AIGA National Board Director and Chair Emerita of the Task Force. During her tenure, Carroll founded and launched several initiatives, including the Design Census Program with Google, Racial Justice by Design Initiative, Diversity and Inclusion Residency, and National Design for Inclusivity Summit with Microsoft. Disagreements over policies and direction led Carroll to publicly resign in an open video letter calling out the organizations’ inability to address internal and external DEI issues.[2] Others, like designer and activist, Amelie Lamont, decided to leave their board positions and wrote a community letter calling for Black designers to leave the organization as it is unsafe for Black designers after several missteps by the organization around race and diversity programs, related communications and other personal experiences.[3] The organization was also put on notice for only recognizing the contributions of Black designers posthumously. It was clear early on that the AIGA wasn’t the place for interaction designers but apparently it isn’t the place for Black designers either.[4]

Failures like this are part of the reason we have seen a crop of more inclusive communities of practice emerge, founded and led by people of color and queer designers. These communities have emerged because of the failures of the larger organizations, that while proclaiming diversity and inclusion, show a face that is predominantly white and, in practice, are less than welcoming to those who don’t fit that stereotypical, outdated model of “designer.”

Read about how Mitzi Okou and Amelie Lamont are creating new spaces for Black designers.

Footnotes

[1] This opinion reflects audited AIGA annuals from a 10 year period to see when digital, new media, multimedia and experience design work appeared and how many projects were awarded recognition compared to print work.

[2] The video from December 2019 is no longer available on YouTube but for a time was public, calling out the AIGA for these issues of equity.

[3] Amélie Lamont, “I’m Leaving AIGA Behind. You Should, Too.,” Medium, July 3, 2020, https://amelielamont.medium.com/im-leaving-aiga-behind-you-should-too-f5fa5548bdf8.

[4] George Aye, “Decolonizing AIGA,” Medium, June 9, 2020, https://medium.com/@george_aye/decolonizing-aiga-a6cc8fb8692e.

Selected Stories

Sasha Costanza-ChockProject type

Kaaren HansonProject type

Ari MelencianoProject type

Mizuko Itoresearch

Boxes and ArrowsProject type

Mithula NaikCivic

Lili ChengProject type

Ovetta SampsonProject type

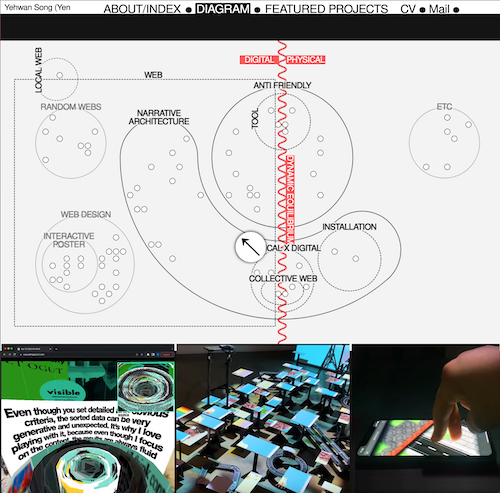

Yehwan SongProject type

Anicia PetersProject type

Simona MaschiProject type

Jennifer BoveProject type

Chelsea JohnsonProject type

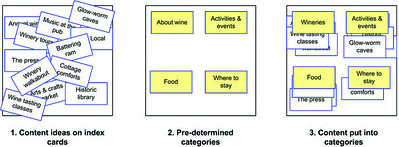

Donna SpencerProject type

Lisa WelchmanProject type

Sandra GonzālesProject type

Amelie LamontProject type

Mitzi OkouProject type

The Failings of the AIGAProject type

Jenny Preece, Yvonne Rogers, & Helen SharpProject type

Colleen BushellProject type

Aliza Sherman & WebgrrrlsProject type

Cathy PearlProject type

Karen HoltzblattProject type

Sabrina DorsainvilProject type

Lynda WeinmanProject type

Irina BlokProject type

Jane Fulton SuriProject type

Carolina Cruz-NeiraProject type

Lucy SuchmanProject type

Terry IrwinProject type

Donella MeadowsProject type

Maureen StoneProject type

Ray EamesProject type

Lillian GilbrethProject type

Mabel AddisProject type

Ángela Ruiz RoblesDesigner