Kaaren Hanson

Changing How Design is Done from the Inside Out

Written by Erin Malone

One of the hardest questions a person can answer is what do you do next when you have reached the top of your field and all the stretch goals you set for yourself? A person could retire, or they can try something new. That’s exactly the question Kaaren Hanson asked in 2014 when coming up to her twelfth anniversary at Intuit. Asking her mentor, Claudia Kotchka, for advice, she advised to either stay and die[1] or move on. So, she left.

Business and design leaders who study business-case-studies looking at how best to bring design thinking into their company have heard the stories about Kaaren Hanson, Design for Delight and the work she spearheaded with Scott Cook, founder of Intuit, and Brad Smith, then CEO of Intuit. But not everyone has heard about the journey that led to these efforts or what has come next in Hanson’s career. Kaaren Hanson received her bachelor’s degree in psychology from Clark University and a PhD in social psychology from Stanford University.

She started her career working for the American Institutes of Research doing research and watching the run up of the dotcom boom from the outside. “Everything fun that was happening, was happening in the dot coms. And I thought, I want to be part of the fun and obviously there’s a need for researchers, so I went to a startup that was funded by American Express and Kleiner Perkins. This was back in the secret, secret, days. We didn’t know the full company name and our paychecks came from a different place. It had a secret name. I didn’t learn what we did until the day I started. I was a part of the design team, I learned everything I know from two amazing designers, Michelle [Sarko] and Mary, they taught me by doing and it was great.”[2] She tells me it was fascinating and a great learning experience. Digging into the product and user needs, she says, “when I got there, I asked 'what are we building?' I remember going out with my CMO and the founder and I asked, ‘how much research was done before we got this funding?’ And they said, ‘oh none’. And I thought, ‘oh my God, this is a house of cards.’ I left after six months (around 2000) and as you know a lot of things blew up in 2000.”[3]

She next went to Remedy Corporation, a company that had been deemed one of the hottest companies of this era. Number one on Business Week’s Hot Growth Companies list for 1996,[4] the company made help desk support software. While there the company was sold to competitor Peregrine Systems and by 2002, they were filing for bankruptcy. “I ended up growing the team and became a user experience leader. We ended up being bought and then it turns out their CFO went to jail for cooking the books. Then we were spun out to a company called BMC Software. So, I had the same office but just kept filling out new healthcare forms. I also kept having to champion design and why it mattered and explaining it to all these different people—new bosses for each new company. After a while they wanted me to spend a lot of time going to Texas. I had a new baby and Intuit had been calling me for a while, so I left and went to Intuit.”[5]

That decision changed the trajectory of her career. From user experience design manager to one of the most visible women in user experience and business as VP of Design Innovation. When Hanson started at Intuit, the company’s main products were Quicken, TurboTax for consumers and QuickBooks for small businesses. It later added Homestead, websites for small businesses and Mint, which soon replaced Quicken.

The company had implemented Net Promoter Score in 2004[6] to gauge customer satisfaction—based on recommending the products to others. But by 2007, NPS had flattened. One of the differentiators internalized by the company, especially executives, was that their products were known for their ease of use.

But as Hanson relates after she started “I was in a central organization that was called Customer Centered Design and I was with Suzanne Pellican, who’s now at Google and Joe O’Sullivan who is on my team now. I remember Intuit was seen as a place where designers went to die. It was horrifying when we realized that was the word on the street. And we decided we were going to be all in and champion design. We had started to do benchmarking and Erica Kindlund had started doing this great benchmarking project looking at QuickBooks versus other competitors. She was being rigorous and super thorough. We started to do this across the board for all our most popular products. What we realized is while Intuit had the name that said we were intuitive; we were no easier to use than other products out there. Maybe a little easier, but it not substantially. I had gotten to know various executives and Scott Cook knew me and he trusted me. I was sharing some of this information with him and other leaders and they brought me into the CEO staff to share this information with them. I remember this very vividly, because it was my first CEO meeting, and I was terrified. I said to them, ‘it turns out we're no easier to use than others. And they were saying, ‘that is not true, that can’t be true. We are Intuit’. And I said, ‘well, no, it’s actually true’. Eventually, they came along to it. Then they said, okay, well then it is all about ease. How do we make this easier to use? At the time process excellence was very much in vogue. The process excellence team got all excited and said, ‘we’re all about ease’. The designers and the process excellence people worked together and we started to knock off things that we thought would improve the ease of use. We found though, that while we improved the ease of use, the net promoter scores did not change.”[7]

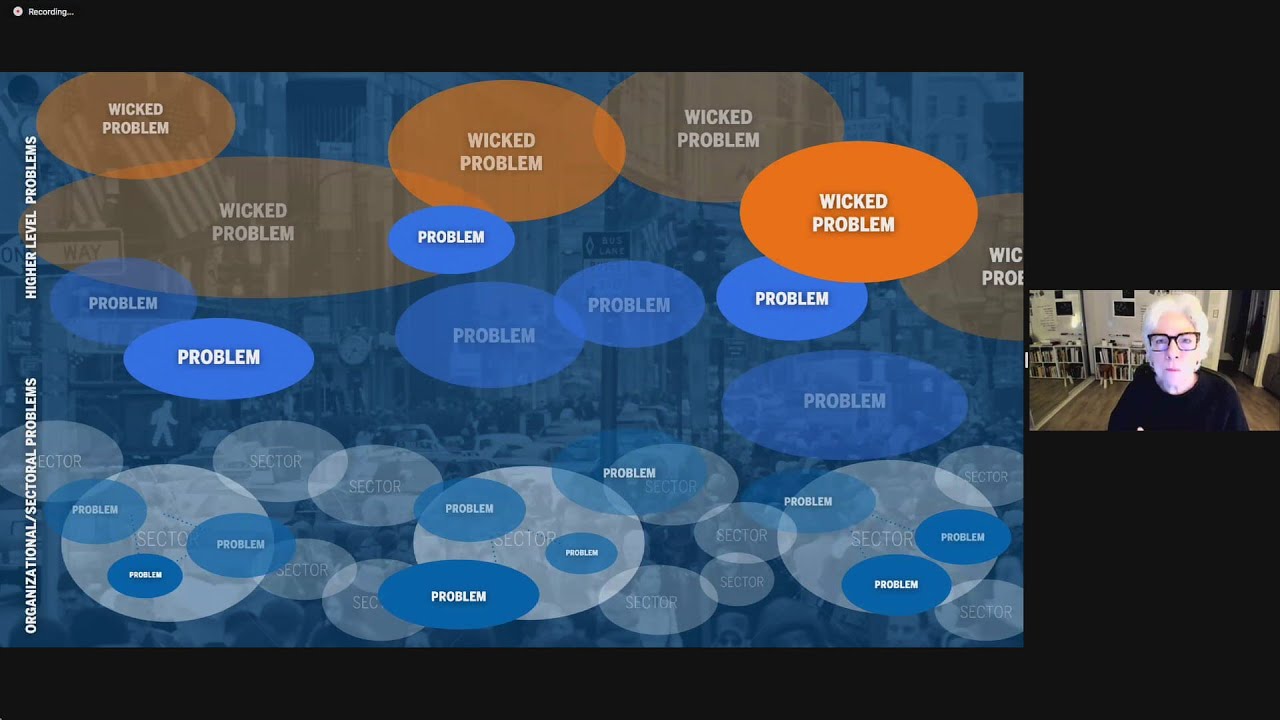

For many companies this would be a death blow to the credibility and ROI of the design team—at a minimum it would remove them from the table as an equal partner. But the executive team didn’t react that way. Instead, they put together a tiger team to brainstorm what is beyond ‘ease’. Hanson told me about that process, “I was a part of that tiger team. There were some general managers on that tiger team. The person in charge of strategy was on that tiger team. Scott [Cook] was a part of that, and we went out and looked at other companies like Nike and Harley Davidson, all the usual suspects. And we came back with what’s beyond ease; it’s positive emotion. This became the foundations for ‘design for delight’.”[8]

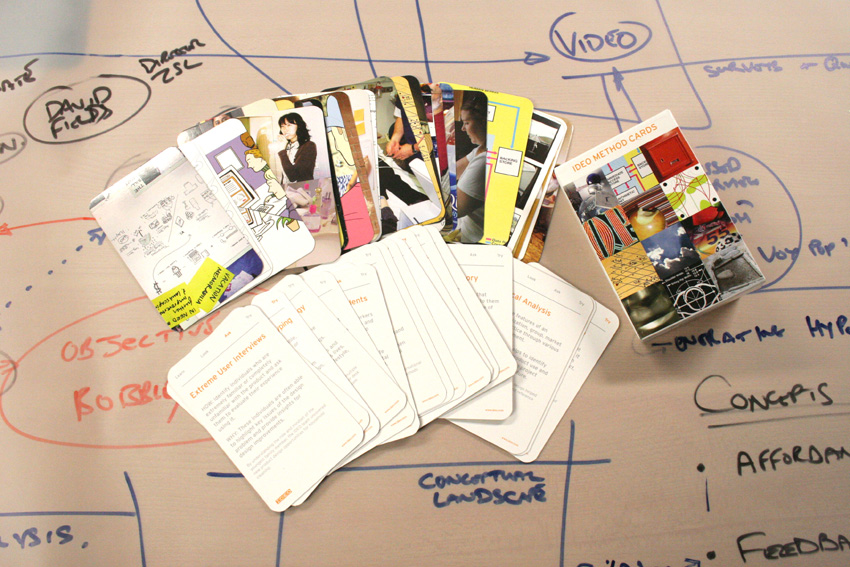

They kicked off the initiative at an executive meeting and had all the attendees brainstorm together about experiences that delighted them. They used that exercise to have everyone viscerally feel that emotion that they wanted their customers to feel. Hanson was tapped by Cook to lead the efforts in the meeting and beyond. She went to the d. school to learn about the process and culture change. She brought in speakers from companies that they admired. Despite executive buy-in, the initiative languished that first year. Most people thought it was just another executive initiative that would be forgotten when the next hot trend came along. But rather than dropping it, they doubled down. Hanson developed a role for coaches to help spread the process through the company. She invited 10 members across the design team to be Innovation Catalysts. These coaches would spend 25% of their time helping any team that wanted to run the Design for Delight (D4D) process. She quickly learned that not everyone is cut out to be a coach. “It has to be someone who thrives on helping others do great work, rather than a person who does great work themselves.”[9]

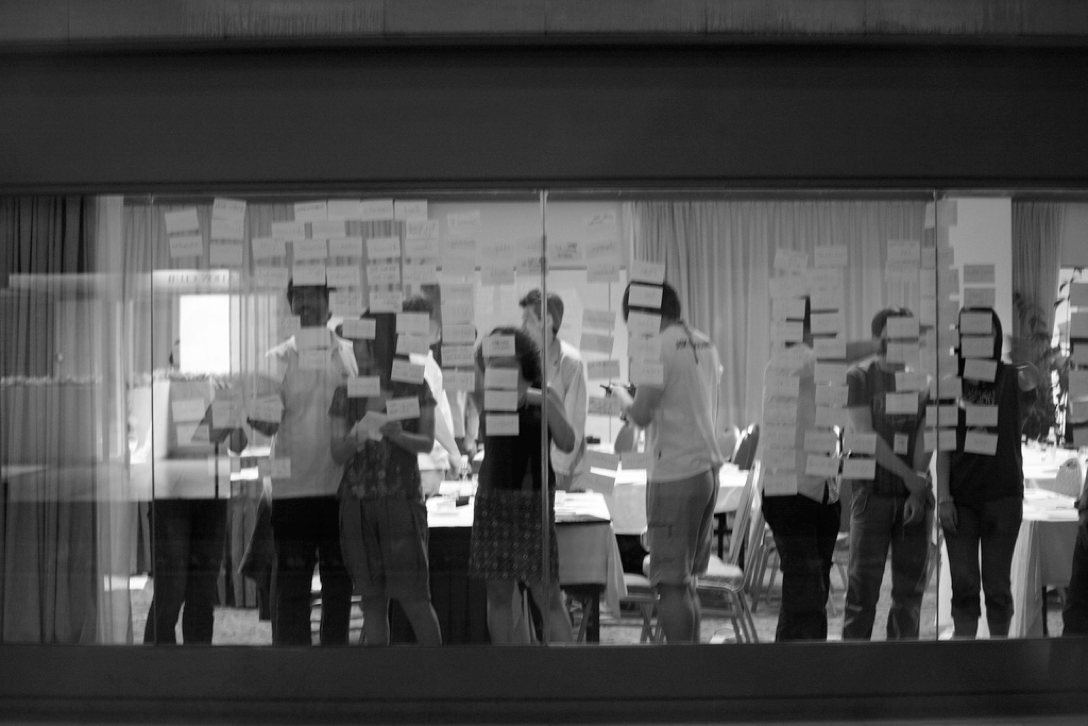

Over the years the Innovation Catalyst program, under the leadership of Suzanne Pellican, grew from 10 to 500 people with a waiting list of 300 and under Wendy Castleman it grew even further. Catalysts came from all roles across the company and help run D4D processes with any team looking to innovate, from product teams to customer care to legal. As someone who has participated in a D4D session, it's an amazing sight to see a cross-functional team brainstorm hundreds of ideas, narrow them down to a select few, rapidly prototype them and bring in real customers to test the concepts with, all in a daylong event.[10] Those concepts were then integrated into roadmaps or used to help define the next set of new ideas.

Everyone coming into the company, eventually ends up being trained in the D4D process, especially designers. The successful outcome of the revamped process, with its Innovation Catalysts, allowed Hanson to add designers across the board both to raise the level of craft as well as raising the ratio of designers to PMs and to developers, more in line with other design driven companies. She also created a more robust career ladder for individual contributor designers as well as design leaders. The IC role goes all the way up to the level of VP without having to move into leadership. The last is raising salaries for women and people of color.

She recalls, “One thing I did that I'm proud of to this day is I focused a lot on salary and compensation for everyone in experience design, and specifically did cuts of the data by gender and race. Every year I would ask for the analysis and would face barriers to getting it. I would escalate, escalate, escalate, and eventually would get the data. And then I would see where there were discrepancies and what we needed to do to fix them. I would then go to the general manager, and I’d say, ‘Okay, these individuals are not where they should be. This is what it’s going to take to adjust them.’ A hundred percent of the time, the general managers would then say, ‘Great, do it.’ What I feel really good about is that those individuals benefit for the rest of their lives from the increase. It’s something I continue to advocate for in my roles. It takes ownership from leaders to elevate situations like these and support parity for more people.”[11]

The program and Hanson’s work across the board changed the culture of the company in transformational ways. In 2010 and 2011, she received the CEO’s Leadership awards for driving transformational change across the company. The implementation of D4D changed how product teams worked, how the design teams worked, it changed the rewards systems and the structure of the organization. In an article from 2015, both Hanson and Wendy Castleman, the innovation catalyst lead at the time, talked about how the success metrics and the stories told about success had to change as well. They cite Thaler & Sunstein’s book Nudge and the approaches in the book as guidance for how behavior of organizations can be changed, not just an individual’s behavior.[12]

The success of the program is partially because they iterated the process, trying small experiments and making changes a little at a time. The combination of being executive sponsored and accepted by first level employees working from the ground up to define the processes also contributed to its success. The CEO at the time, Brad Smith and Hanson credit this approach as to why the company was able to easily catch up with products in the mobile market when they were originally behind their competitors.

The story of the program under Scott Cook and Kaaren Hanson’s leadership has been included in successful business and design case studies across leading business magazines and several books including Solving Problems with Design Thinking (2013, Liedtka et al); Creative Confidence (2013, Kelly & Kelly); Scaling Up Excellence (2014, Sutton & Rao) and Moments of Impact: How to design strategic conversations (2014, Ertel & Solomon).

When I asked her how she knew when it was time to leave, she shared with me, “When we first started doing this Design for Delight bit, we came together and made a list of what it would mean when we were successful, when we had achieved our vision. There were certain things including being named in the [DMI] design driven company's list and speaking with the CEO at some business forum. At the time I had watched A.G. Lafley [then P&G’s CEO] and Claudia Kotchka [then P&G’s VP of Design Innovation] talk about design at the Illinois Institute of Design and I thought, we’ve got to be on that stage. The year that I left, Scott and I went to the Illinois Institute of Design and spoke just like Lafley and Kotchka had. Brad and I went to this big business forum where we talked about design and how that drives business value. And we were put on the design driven companies list and were tracked as part of that. We had design leaders at all the general manager’s tables. Something like 70% of the company was engaged in Design for Delight. And we had a waiting list of 500 people for the innovation catalyst role.”[13]

Hanson left the company and decided to do something different, something on a smaller scale. “I found a startup because I wanted to do the opposite. Intuit was a big company. I bought a bicycle and I biked to work every day and back. There were 300 total people, the team of designers were four. I was getting in there doing design, which I hadn't done in years. It was scrappy and crazy, and terrifying, and exhilarating. I never laughed more in my life. I grew the team to the size of 24 or so.”[14]

That startup was Medallia, and she did a 2-year stint and moved on to Facebook where she thought she could be in a big company with a startup atmosphere. But like many others she left when it started to feel less good. On the other hand, she came to realize that she had a lot of passion for finance and a lot of experience because of her years at Intuit. She wanted to move into a company where she could help people with their finances and the anxiety many feel about money, financial products, and banking.

That next finance company was Wells Fargo. She carefully shares that her team couldn’t do a lot of the things she wanted to do because of being under a consent order. These are restrictions that were placed on the company back in 2015 for unfair billing practices associated with various identity protection products[15]. She shared with me that when she went to the bank, she didn’t know what that meant, but ultimately, it meant her team couldn’t ship anything. It’s hard to stay excited about doing great work when you can’t ship the work, so when J.P. Morgan Chase called, she jumped.

When we spoke in 2022, she had just started as Chief Design Officer for the global finance firm—a role she has since left. At the time she was in growth mode for the team. She built up a robust team and brought into play what she learned in her previous roles, like adjusting ratios of designers to other team members.

As the head of a global design practice, she has influence over diversity in hiring and as a mentor she specifically goes out of her way to coach her team before important meetings, to call out ideas offered by women when they’re repeated by men and to generally try to level the playing field. We talked about the perceptions of hiring teams when reviewing men versus women. “When I was interviewing some candidates for a particular senior role and we came down to the top two, one was a woman who’d been doing this job for many years. The other was a guy who had never done this job, but he was thought of highly by somebody’s friend from business school. So, I raised this in a meeting, and I said, ‘men are given jobs based on potential, whereas women are looked at for their performance’. Then I sent a follow up note about it, and they said, ‘that’s interesting. We’re making the offer to him.’ And I thought, ‘wow, that totally failed.’”

“Sometimes I fail, but I work to make sure I’m still around for the next conversation. One thing that I’ve done that has worked in the past was acknowledging that we’re taking a risk. Because the research I’ve read is that people are more willing to take risks people that are like them as opposed to people not like them. I think there's something too about acknowledging the discomfort people are going to have and just bringing it out because we know that’s a dimension that matters, even if they don’t know that it’s a dimension that's impacting them.”

"I’m here to create conditions in which people are doing the best work of their lives. They’re creating great experiences that have a business impact. Those great experiences mean there’s benefit to the customer! That's a core part of that great experience. It’s good for customers and it’s good for the employees. I feel like we are all so lucky being in these roles because we get to help people have empathy for each other. We get to help people have more fun at work and have more impact on people who are customers in good ways. The fact that I get to champion making this happen is such a gift.”[16]

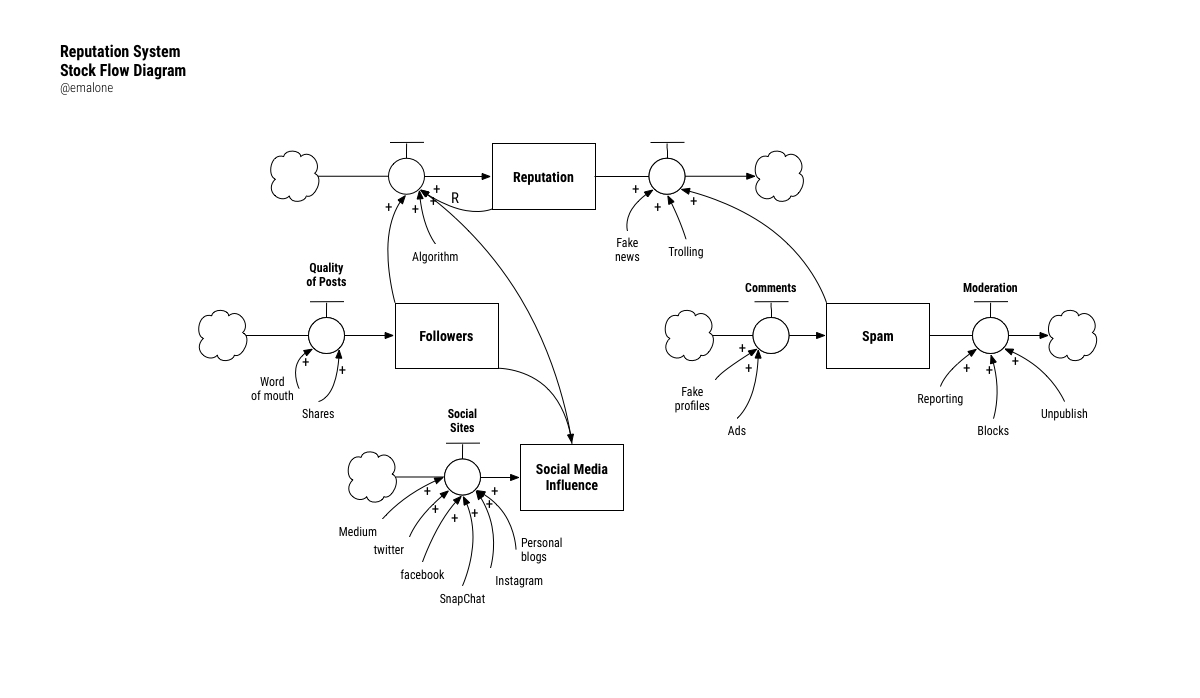

The Principles of Design for Delight at Intuit.

Image © Intuit.

Footnotes

[1] There was a time when Intuit was listed as the place in Silicon Valley where designers went to die. Employees work there for 10, 20 even 30 years unlike almost every company in the valley where 5 years is ancient. This speaks to the positive culture there despite the negative jokes.

[2] Kaaren Hanson, A Conversation with Kaaren - interview with Erin Malone, interview by Erin Malone, May 4, 2022.

[3] Hanson, Interview.

[4] Amy Barrett, “05/27/96 HOT GROWTH COMPANIES,” archive.ph, January 19, 2013, https://archive.ph/VK4hS#selection-159.402-159.447.

[5] Hanson, Interview.

[6] Roger L. Martin, “The Innovation Catalysts,” Harvard Business Review, June 2011, https://hbr.org/2011/06/the-innovation-catalysts.

[7] Hanson, Interview.

[8] Hanson, Interview.

[9] Wade Roush, “Xconomy: Intuit Goes All out to Solve the Innovator’s Dilemma. Is It Working?,” Xconomy, November 6, 2012, https://xconomy.com/san-francisco/2012/11/06/intuit-goes-all-out-to-solve-the-innovators-dilemma-is-it-working.

[10] Intuit was a client of when I was a partner in the consulting practice Tangible UX from 2008-2019 and I participated in several D4D sessions with the different teams we worked with over the years.

[11] Hanson, Interview.

[12] Jan Schmiedgen, “From Stories and Metrics,” This is Design Thinking!, May 13, 2015, https://thisisdesignthinking.net/2015/05/intuit-design-for-cultural-change/.

[13] Hanson, Interview.

[14] Hanson, Interview.

[15] Bram Berkowitz, “A Guide to All of Wells Fargo’s Consent Orders,” The Motley Fool, October 10, 2021, https://www.fool.com/investing/2021/10/10/a-guide-to-all-of-wells-fargos-consent-orders/.

[16] Hanson, Interview.

Kaaren Hanson Bibliography

Barrett, Amy. “05/27/96 HOT GROWTH COMPANIES.” archive.ph, January 19, 2013. https://archive.ph/VK4hS#selection-159.402-159.447.

Burnett, Richard. “A Mobile App Refresh Whose Time Has Arrived - Wells Fargo Stories a Mobile App Refresh Whose Time Has Arrived.” Wells Fargo Stories, November 17, 2020. https://stories.wf.com/a-mobile-app-refresh-whose-time-has-arrived/.

Glasson, Chelsey, and Ian Swinson. “Which Path Is for Me? The Emerging Role of vp of UX.” User Experience Volume 11, no. Issue 3 (2012): 14–16. www.uxpa.org.

Hanson, Kaaren. A Conversation with Kaaren - interview with Erin Malone. Interview by Erin Malone, May 4, 2022.

———. “How to Save a Good Design from Its Imminent Death.” Fast Company, April 24, 2014. https://www.fastcompany.com/3029425/how-to-save-a-good-design-from-its-immanent-death.

Kelley, Tom, and David Kelley. “Chapter 6: Team | Creative Confidence by Tom & David Kelley.” www.creativeconfidence.com. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://www.creativeconfidence.com/chapters/chapter-6.html.

Liedtka, Jeanne. “Why Design Thinking Works.” Harvard Business Review, August 28, 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/09/why-design-thinking-works.

Liedtka, Jeanne, and Andrew King. “Use ‘Design Thinking’ to Reach Customers.” Washington Post, May 4, 2014, sec. Capital Business. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/capitalbusiness/use-design-thinking-to-reach-customers/2014/05/02/6e7a99c0-d05c-11e3-937f-d3026234b51c_story.html.

Martin, Roger L. “The Innovation Catalysts.” Harvard Business Review, June 2011. https://hbr.org/2011/06/the-innovation-catalysts.

O’Brien, Chris. “How Intuit Became a Pioneer of ‘Delight.’” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 2013. https://www.latimes.com/business/la-xpm-2013-may-10-la-fi-tn-intuit-pioneer-delight-20130509-story.html.

Roush, Wade. “Xconomy: Intuit Goes All out to Solve the Innovator’s Dilemma. Is It Working?” Xconomy, November 6, 2012. https://xconomy.com/san-francisco/2012/11/06/intuit-goes-all-out-to-solve-the-innovators-dilemma-is-it-working.

Schmiedgen, Jan. “From Stories and Metrics.” This is Design Thinking!, May 13, 2015. https://thisisdesignthinking.net/2015/05/intuit-design-for-cultural-change/.

Smith, Brad D. “Love at First Use: Three Tips for Building Awesome Products.” www.linkedin.com, January 10, 2013. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/20130110155158-1940438-love-at-first-use-three-tips-for-building-awesome-products.

Selected Stories

Sasha Costanza-ChockProject type

Kaaren HansonProject type

Ari MelencianoProject type

Mizuko Itoresearch

Boxes and ArrowsProject type

Mithula NaikCivic

Lili ChengProject type

Ovetta SampsonProject type

Yehwan SongProject type

Anicia PetersProject type

Simona MaschiProject type

Jennifer BoveProject type

Chelsea JohnsonProject type

Donna SpencerProject type

Lisa WelchmanProject type

Sandra GonzālesProject type

Amelie LamontProject type

Mitzi OkouProject type

The Failings of the AIGAProject type

Jenny Preece, Yvonne Rogers, & Helen SharpProject type

Colleen BushellProject type

Aliza Sherman & WebgrrrlsProject type

Cathy PearlProject type

Karen HoltzblattProject type

Sabrina DorsainvilProject type

Lynda WeinmanProject type

Irina BlokProject type

Jane Fulton SuriProject type

Carolina Cruz-NeiraProject type

Lucy SuchmanProject type

Terry IrwinProject type

Donella MeadowsProject type

Maureen StoneProject type

Ray EamesProject type

Lillian GilbrethProject type

Mabel AddisProject type

Ángela Ruiz RoblesDesigner