Ángela Ruiz Robles

Inventor of the first multimedia e-book

Written by Erin Malone

It’s said that in 1971, Michael Hart invented the eBook while he was at the University of Illinois. He created an electronic document of the United States Declaration of Independence by inputting it into a Xerox Sigma V mainframe as plain text. The computer was just one of a few linked together on the ARPANET. This became the seed for Project Gutenberg whose mission was to digitize and archive books in the public domain as well as those with cultural importance.

But before Michael Hart, there was the Spanish schoolteacher, Ángela Ruiz Robles, who prototyped and patented the Enciclopedia Mecanica, or the Mechanical Encyclopedia. This was a mechanical multimedia concept that would deliver text, graphics, audio, and other media to replace multiple books and is considered by some, the first electronic book.

Robles noticed that students had to carry a lot of books to school and wanted to come up with a device that could replace them all and add to them through replaceable audio and video. One of her goals was to also eliminate the bulk of contemporary encyclopedias and to improve the timeliness of content that went out of date as soon as it was published in books. The device also included a calculator, a light for night reading, and a magnifier for zooming into things.

Born near the turn of the century (1895) Robles came from a wealthy family in Villamanin, Leon, Spain. She trained as a teacher at the School of Teachers in León and taught classes in shorthand, typing and business accounting in her early teaching career. In 1934 she became manager of the Escuela de Niñas del Hospicio - the National Girls School Orphanage, where she taught unwed, pregnant, and abandoned girls needing skills to integrate into society.

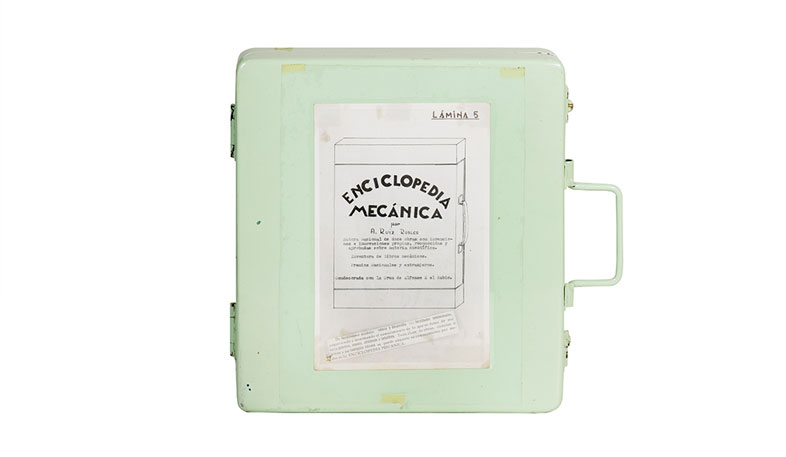

The prototype of the Mechanical Encyclopedia invented by Ángela Ruiz Robles in 1948. The prototype was completed in the 1960's from the patent drawings. The system included reels of content that could be customized by educators, images, sound and magnifiers for enlarging content.

Ángela Ruiz Robles surrounded by her students.

In the 1940’s, Robles founded the Elmaca Academy, with her 3 daughters, providing classes in business management classes. The school became a hub of social activity with literary gatherings, religious processions and food distributions.

Robles would later move to Galicia in the late 1950s and work as a national teacher and director of the Ibañez Martín Center where she taught until her retirement. Robles spent 16 years there teaching students and after her workday she would visit those needing extra help in their homes. She also regularly taught adult villagers, many who couldn’t read or write.

According to the Foundation Telefonica 2015 expo on Robles and her work, Robles was an anomaly in her time in Spain. At the beginning of the 20th century only 25% of the female population could read and write and, in most cases, women were housewives with no higher education access and manual unskilled labor the only work available outside the home.[1]

When she was in her forties she began writing and publishing textbooks and over the next few years she authored 16 books on spelling, typing, shorthand, grammar, history, geography, typing, science, orthography, mechanics and linguistics.

Already an inventor, she had invented a shorthand system in 1916 and perfected it in the 1940’s; she invented the Mechanical Encyclopedia for her students in 1948 and patented the design in 1949. She was looking for a way to make education more accessible and inviting. The device had multiple content reels that could be in any language or on any subject. She imagined that teachers could produce their own content for the reels.

The first patent (1949) was described as a mechanism with buttons that when activated and pressed, displayed learning materials. The second patent (1962) was for a modified design without the buttons but included reels that presented learning materials, including illustrations, ability to read in the dark, spoken (audio) descriptions of each topic and a magnifying glass.

The description of the device from the original patent (translated from Spanish):

“The subjects are stored in the right-hand part, passing beneath a transparent, unbreakable sheet; these can be enlarged, and the books can be illuminated so that they can still be read if there is otherwise no light. The right-hand and left-hand sides of the section the materials pass through contain two coils in which the books the user wants to read in any language are placed; moving these allows all the topics to pass by, stopping as and when the user wishes, or to be collected. The coils are automatic and can be moved from the box and expanded, so that the whole subject remains visible. The device may be placed either on a table (like an ordinary book) or perpendicular to it, which is handy for the user, since it eliminates a great deal of mental and physical effort. All the components are replaceable. When closed, it is the same size as an ordinary book, and easy to handle. For authors and publishers, it greatly reduces production costs, for it does not require either paste or binding, and can be printed either in a single print run, or section by section (if there are several)—a procedure of value to all.”

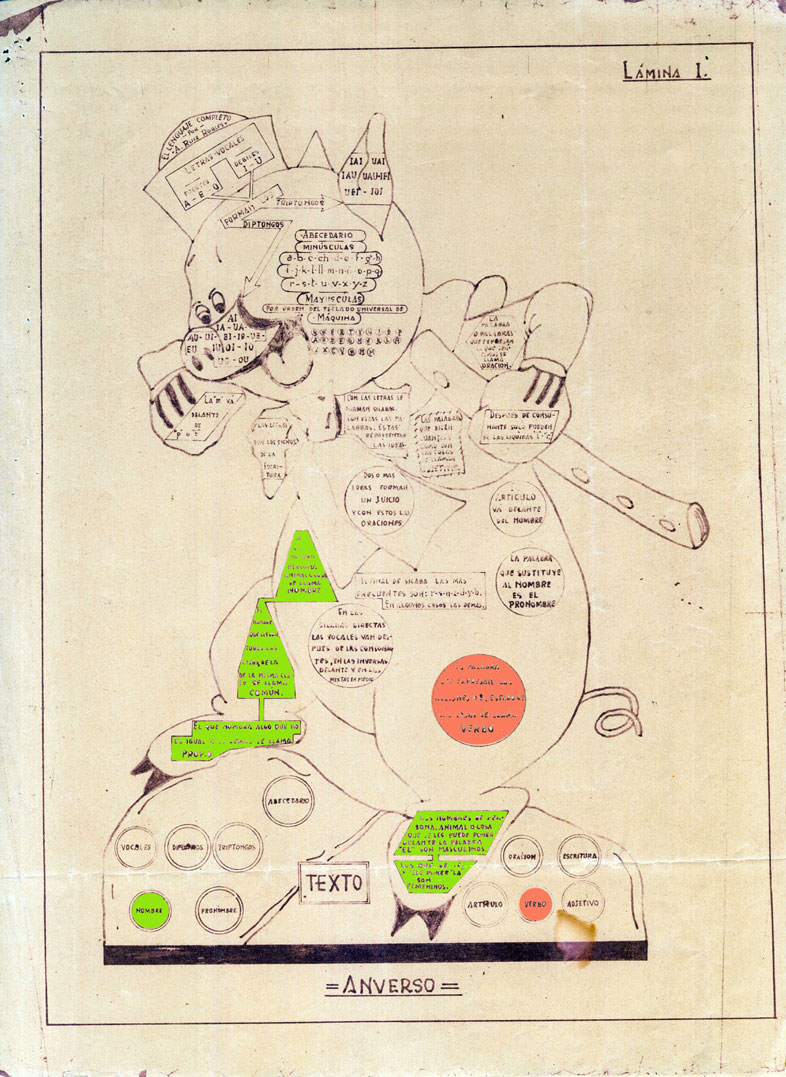

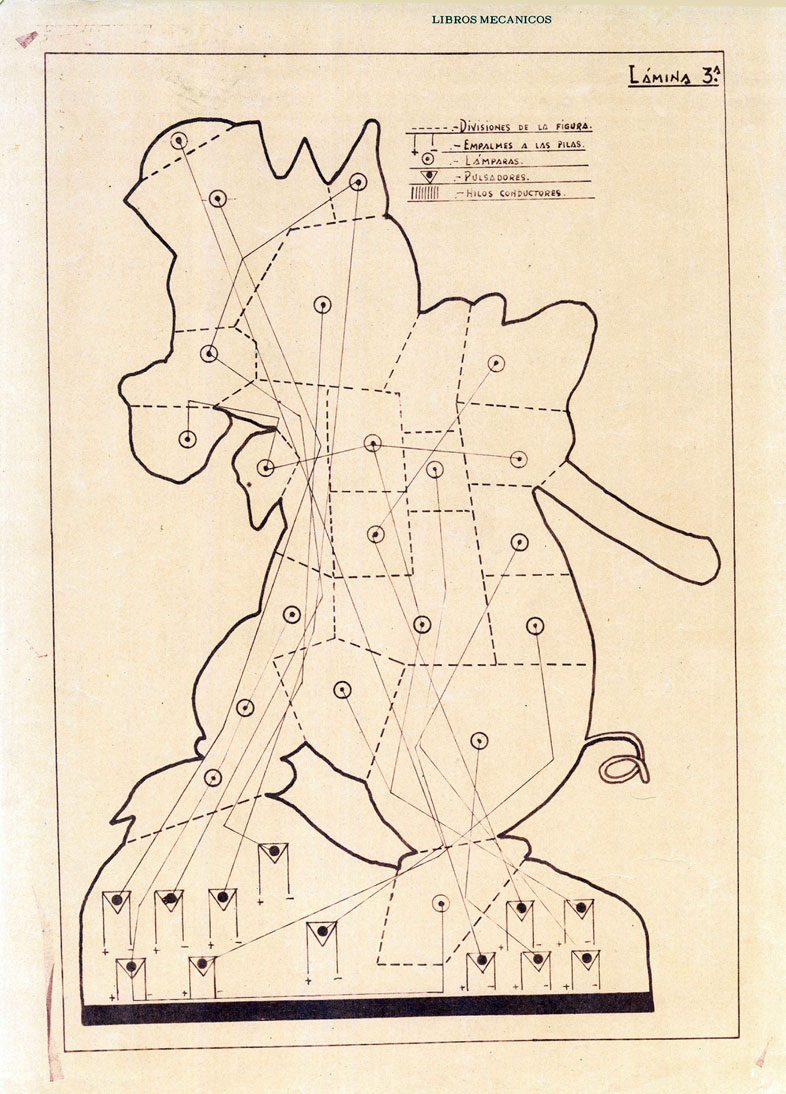

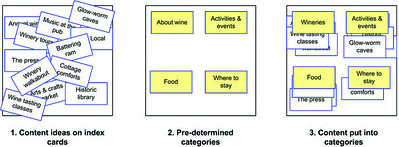

Drawings for how interaction and hypertext would work in sections of the Mechanical Encyclopedia. Highlighted version of the interaction - When a student selects an item it highlights and shows the correct information or additional information. This was an early version of hypertext. The far right image shows the electronic connections diagram to make the interactive, highlights work.

In her drawings, she included two images for teaching grammar and math which showed a flute-playing pig on which various questions and answers were drawn. If the user clicked ‘verb’ then a word that expressed that action would light up. This was an early example of hypertext linking. Her drawings also included the electrical diagrams that would respond when someone touched a section of the “screen” and what would happen electronically in response.

According to Santiago Asensio, the manager of the Angela Ruiz Robles catalog and the invention of the mechanical book exhibit, “Ángela did not like traditional books, she thought it was more interesting to see and touch than to turn pages.”

Her inventive nature extended beyond the mechanical encyclopedia and can be seen in some of her published books as well. In her book Atlas Cientifico Grammatical, she created a fold-out book that showed both Castilian grammar and Spanish geography in ways that allowed the reader to see all the information and their relationships at the same time, rather than in sequential page order. She imagined the contents of lessons in spelling, phonetics and syntax all related to the country’s geography in a way that we would currently think of as hyperlinks. The author of an article on Robles likens the work to ‘an interactive map that links in Wikipedia to Google translate - making relationships between language with geographical points.’[2]

The prototype of the Mechanical Encyclopedia which was shown in the exhibition about Robles and her work as an inventor.

Despite multiple trips to Madrid to secure funding, she was unable to manufacture the device. But she was able to finally create a prototype in 1962 and it is currently in the National Museum of Science and Technology in A Coruna, Spain. After her retirement, Robles spent time evangelizing her invention, giving interviews, talking to potential funders, publishers, and even official organizations in multiple countries. She brought her work to competitions and exhibitions, often the only women inventor at these events. She rejected a proposal to license her patents to the US in 1970, because she wanted her inventions to be developed in Spain and to benefit the people of Spain.

In an interview that Robles gave about her invention, she says, “It is a book that, closed, does not bulk up more than a case or wallet the size of an ordinary book. Its weight is negligible. Open is easy to use and can be used in any shape or form and also be on any movie or television screen. They can carry sound with an explanation of topics in an intuitive, practical, attractive, and entertaining way.”

Robles was concerned with developing and exploring new pedagogy for teaching beyond the book, and her inventions, although limited by the technologies of the times, show her thinking about concepts around hypertext, conceptual and semantic relationships, and delivering learning through multiple media formats that are eerily similar to the work that will be done in the 1980’s by Kristina Hooper and Sueann Ambron for the Apple Multimedia lab. Robles’s approach, like Hooper and Ambron’s, thought about new ways to bring content into education. Using Hypercard, video, and sound, as well as hypertext to bring together content in new relationships, Hooper and Ambron had the luxury of delivery media like the computer and CD-ROMs where Robles used audio and image reels and electrical circuits to give user’s feedback when accessing hypertext links. Robles was definitely ahead of her time for both the ebook but also rich, multimedia teaching environments.

Her work was eventually recognized by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Economy in Spain in 2013, and in 2018 Madrid named a street after her. She died in 1975.

Footnotes:

[1] “La Enciclopedia Mecánica de Doña Angelita,” Espacio Fundación Telefónica, 2015, https://espacio.fundaciontelefonica.com/evento/la-enciclopedia-mecanica-de-dona-angelita/.

[2] Mar Abad, “Ángela Ruiz Robles: La Española Que Vislumbró La Era Digital En Los Años 40,” Yorokobu, June 21, 2015, https://www.yorokobu.es/angela-ruiz-robles/.

Bibliography

- Abad, Mar. “Ángela Ruiz Robles: La Española Que Vislumbró La Era Digital En Los Años 40.” Yorokobu, June 21, 2015. https://www.yorokobu.es/angela-ruiz-robles/.

- admin. “Biography of Angela Ruiz, Spanish Inventor.” Salient Women, June 2020. https://www.salientwomen.com/2020/06/01/biography-of-angela-ruiz-spanish-inventor-scientist/.

- Garcia, Rosa Millan. “Rosa Millán García En Femenino: Ángela Ruiz Robles En WIKIPEDIA, Celebrando El 8 de Marzo.” Rosa Millán García En Femenino, March 5, 2012. http://rosamillangarcia.blogspot.com/2012/03/angela-ruiz-robles-en-wikipedia.html?m=1.

- GRANDAL, DANIEL GONZALEZ DE LA RIVERA. “Los Orígenes Hispanos Del Libro Electrónico: Ángela Ruiz Robles O La Innovación al Educar.” El Año de Turing, January 17, 2013. https://blogs.elpais.com/turing/2013/01/los-origenes-hispanos-del-libro-electronico-angela-ruiz-robles-o-la-innovacion-al-educar.html.

- Heredia, Raquel Pintado. “Ángela Ruiz Robles (1895-1975).” Mujeres con ciencia, May 25, 2017. https://mujeresconciencia.com/2017/05/25/angela-ruiz-robles-1895-1975/.

- Jones, Sam. “Madrid Names Street after Female Inventor of Mechanical ‘Ebook.’” the Guardian, February 25, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/25/madrid-names-street-after-female-inventor-of-mechanical-ebook.

- Espacio Fundación Telefónica. “La Enciclopedia Mecánica de Doña Angelita,” 2015. https://espacio.fundaciontelefonica.com/evento/la-enciclopedia-mecanica-de-dona-angelita/.

- Regueiro, Luis Valle. “Ángela Ruíz Robles | Álbum de Mulleres | Culturagalega.org.” culturagalega.gal, 2007. http://culturagalega.gal/album/detalle.php?id=87.

- Staff, History Computer. “Angela Ruiz Robles - Complete Biography, History and Inventions.” History-Computer, January 4, 2021.

https://history-computer.com/angela-ruiz-robles-complete-biography/. - Stephanie. “ALD21: Ángela Ruiz Robles, Writer and Inventor – Ada Lovelace Day.” findingada.com, October 12, 2021. https://findingada.com/blog/2021/10/12/ald21-angela-ruiz-robles-writer-and-inventor/.

Selected Stories

Sasha Costanza-ChockProject type

Kaaren HansonProject type

Ari MelencianoProject type

Mizuko Itoresearch

Boxes and ArrowsProject type

Mithula NaikCivic

Lili ChengProject type

Ovetta SampsonProject type

Yehwan SongProject type

Anicia PetersProject type

Simona MaschiProject type

Jennifer BoveProject type

Chelsea JohnsonProject type

Donna SpencerProject type

Lisa WelchmanProject type

Sandra GonzālesProject type

Amelie LamontProject type

Mitzi OkouProject type

The Failings of the AIGAProject type

Jenny Preece, Yvonne Rogers, & Helen SharpProject type

Colleen BushellProject type

Aliza Sherman & WebgrrrlsProject type

Cathy PearlProject type

Karen HoltzblattProject type

Sabrina DorsainvilProject type

Lynda WeinmanProject type

Irina BlokProject type

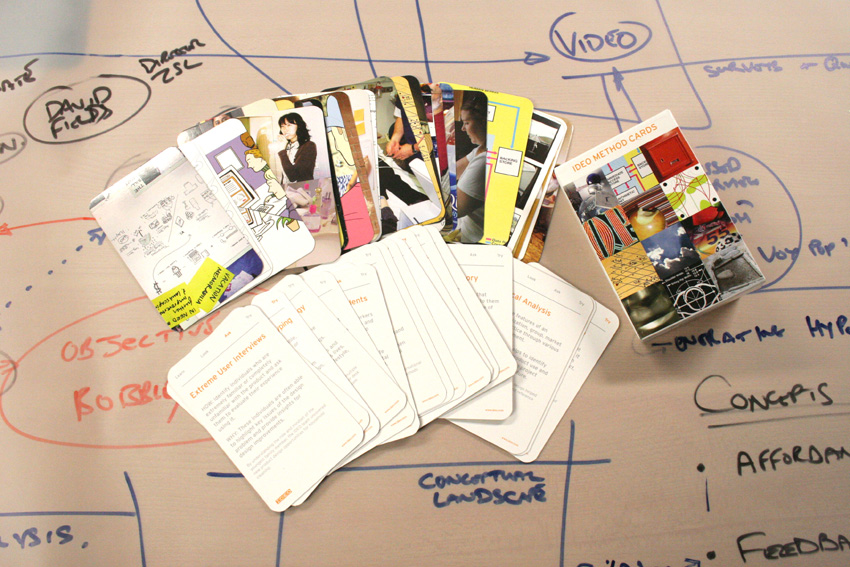

Jane Fulton SuriProject type

Carolina Cruz-NeiraProject type

Lucy SuchmanProject type

Terry IrwinProject type

Donella MeadowsProject type

Maureen StoneProject type

Ray EamesProject type

Lillian GilbrethProject type

Mabel AddisProject type

Ángela Ruiz RoblesDesigner