Ray Eames

Written by Erin Malone

Ray was born in Sacramento California in 1912 and studied art with Hans Hoffman at the Art Student League in Manhattan in the 1930’s and dance with Martha Graham. She considered herself both a painter and a sculptor — interested in structure, form, color and collage. In 1940, after the death of her mother, she attended the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where she met architect and head of the design department, Charles Eames. They were married in 1941 and returned to California, moving to LA.

Working with Charles, she also developed the graphic design pieces used to promote their design practice and she was the cover designer for more than 20 issues of the Arts and Architecture journal during the 1940s.

Ray and Charles’ skills were complementary and covered a breadth of disciplines — furniture, graphic design, textiles, film, architecture and objects like furniture and toys. Ray’s early work, as a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group of the late 1930’s, explored sculptural and spatial structures, abstract forms, geometry and color. Many of the kinds of things the modernist artists of the time were exploring.

Ray developed the prototypes and processes of bending and shaping plywood into biomorphic curves for various expressive sculptures. This work became the inspiration for their most famous creations — the bent plywood chair. While Charles brought the technical skills to the table, it was Ray who brought the life and expression and out-of-the-box thinking to their work.

The Eameses viewed their life as a creative process and brought this thinking and attitude into the work they did. They worked as partners from 1941 until 1978 (Charles’s death), creating, in collaboration with those in their office, a wide range of furniture and other products, including toys. Ray was often referred to in a subservient fashion, as “the wife supporting her husband’s ventures” but she was an equal partner in the work—this is typical for husband-wife creative partnerships and how they were referenced during this era. We can see evidence of this attitude in a video clip of the 1950’s television show “NBC’s Home Show” which featured the work of the Eameses. The host Arlene Francis defers to Charles and minimizes the work of Ray throughout her introduction and series of questions posed to the pair.[1] Another overlooked fact was that Ray Eames worked instead of being a homemaker as expected of women of the time.

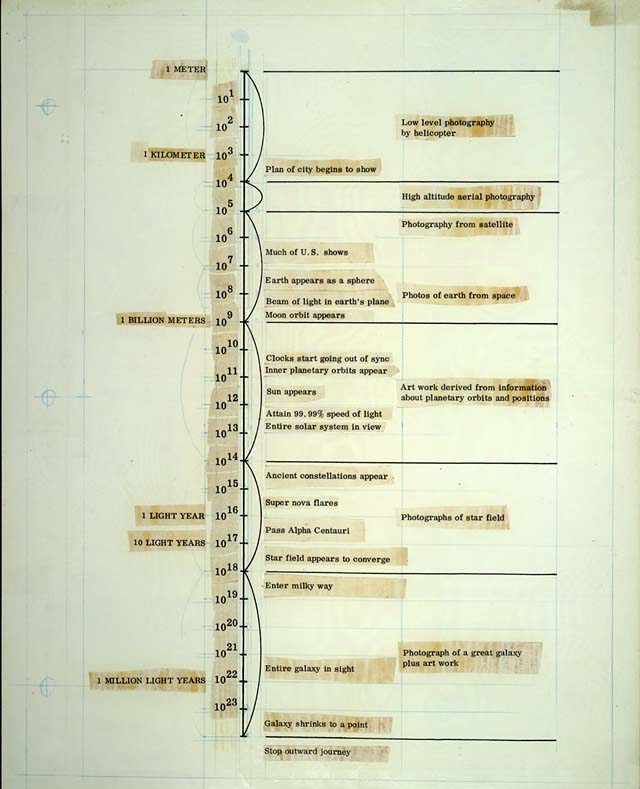

The Eameses also became known for designing exhibitions and co-directed over 175 short films, slide shows, and multimedia presentations. They ranged in topic from the world of Franklin and Jefferson to advanced mathematical explanations to the scientific exploration of scale in the “Powers of Ten.” The exploration into film helped them explore an idea, work out the presentation and the layers of information and understand a process or theory. The Eameses often carried an idea through multiple versions in order to find the right approach to a problem.

In 2002, on the Eames Office website, Lucia Dewey Eames wrote:

“A film could be a model, not simply a presentation of an idea, but a way of working it out. Looking back at the way the office worked, there is a constant sense that the best way to understand a process was to carry it all the way through. For example, in the creation of the project that became the film “Powers of Ten,” first came a test known as “Truck Test,” then the production of “Rough Sketch” (8 minutes; color, 1968), which was a model of the idea of the journey in spatial scale. Only by carrying the idea all the way through could one see the right way to approach the problem. And, indeed, the final version of “Powers of Ten” (9 minutes; color, 1977) has quite a few differences. But both films are models in a more important sense: they are models of the idea of scale. Because such Eames models managed to capture the essence of the problem, they were in fact quite satisfying in their own right.” [2]

In an interview from the early 2000's in ISdesigNET magazine, Charles and Ray’s grandson, Eames Demetrious said:

“There may be a tendency to assume the films are a charming footnote: Furniture designers making films. But that is not how it was, not how Charles and Ray saw it at all. For them, the films were an intrinsic part of the process.”

“The Powers of Ten,” perhaps their most successful film, is one such model into the nature of scale. The first version, developed in 1968 for the annual meeting of the Commission on College Physics, went under the title, “A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of the Universe.” (8 minutes; color, 1968). In 1977, with the help of Philip Morrison, professor of physics at MIT, they updated and refined the work under the new title, “The Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero” (9 minutes; color, 1977). The film sought to visualize the relative size relationships of elements through space and time and expose what happens when you add another zero to the equation.

“The ‘Powers of Ten’ also represents a way of thinking—of seeing the interrelatedness of all things in our universe. It is about math, science and physics, about art, music and literature. It is about how we live, how scale operates in our lives and how seeing and understanding our world from the next largest or next smallest vantage point broadens our perspective and deepens our understanding.” [3]

—Powers of Ten website, circa 2002

Ray was responsible for creating the data visualization translations for all their films, which allowed for easily digestible information, as well as art directing and designing the sets. Together they shared a fascination with structure, a commitment to “getting the most from the least” (a principle of the modern movement in architecture).

Footnotes

[1] “America Meets Charles and Ray Eames,” www.youtube.com, November 23, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IBLMoMhlAfM

[2] Lucia Dewey Eames on The Powers of Ten and film as a model from an early 2002 version of the Eames Office website. The site is no longer up and the exact pages in Wayback Machine have not been archived.

[3] 2002 version of the Powers of Ten website. The site is no longer online.

Ray Eames working with freeform sculptural shapes.

Original publication: unknown

One of the most famous bent wood chairs by Ray and Charles Eames. Sailko, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

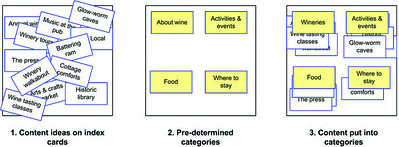

Chart plotting sequences of “Powers of Ten”, Library of Congress Eames Collection.

Bibliography

- Beaman, Kelly. “The Eames Office Puts Ray Eames’s Design Contributions in Context.” Metropolis, March 27, 2022. https://metropolismag.com/profiles/ray-eames-collaborations-eames-demetrios/.

- Cohn, Jason, and Bill Jersey, eds. “Eames: The Architect and the Painter (trailer).” First Run Features, 2011. https://www.amazon.com/Eames-Architect-Painter-Charles/dp/B08QN2XB44/ref=tmm_aiv_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=.

- Eames, Ray, and Charles Eames. “The Films of Charles & Ray Eames, Vol. 1: The Powers of 10.” DVD. IMAGE ENTERTAINMENT, 2000.

- Kirkham, Pat. Charles and Ray Eames : Designers of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Mit Press, 1998.

- Malone, Erin. "Learning from the Powers of Ten." Boxes and Arrows. March 10, 2002.

- Morrison, Philip, Phylis Morrison, and Charles And. Powers of Ten : A Book about the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero : Based on the Film Powers of Ten by the Office of Charles and Ray Eames. New York: Scientific American Library, 1994.

- Sellers, Libby. WOMEN in DESIGN : Pioneers in Architecture, Industrial, Graphic and Digital Design from The... Twentieth Century to the Present Day. S.L.: White Lion Pub, 2021.

- The Work of Charles and Ray Eames: A Legacy of Invention. Exhibition - 1999-2002. Online catalog and exhibition of the Eameses work donated to the Library of Congress.

Selected Stories

Sasha Costanza-ChockProject type

Kaaren HansonProject type

Ari MelencianoProject type

Mizuko Itoresearch

Boxes and ArrowsProject type

Mithula NaikCivic

Lili ChengProject type

Ovetta SampsonProject type

Yehwan SongProject type

Anicia PetersProject type

Simona MaschiProject type

Jennifer BoveProject type

Chelsea JohnsonProject type

Donna SpencerProject type

Lisa WelchmanProject type

Sandra GonzālesProject type

Amelie LamontProject type

Mitzi OkouProject type

The Failings of the AIGAProject type

Jenny Preece, Yvonne Rogers, & Helen SharpProject type

Colleen BushellProject type

Aliza Sherman & WebgrrrlsProject type

Cathy PearlProject type

Karen HoltzblattProject type

Sabrina DorsainvilProject type

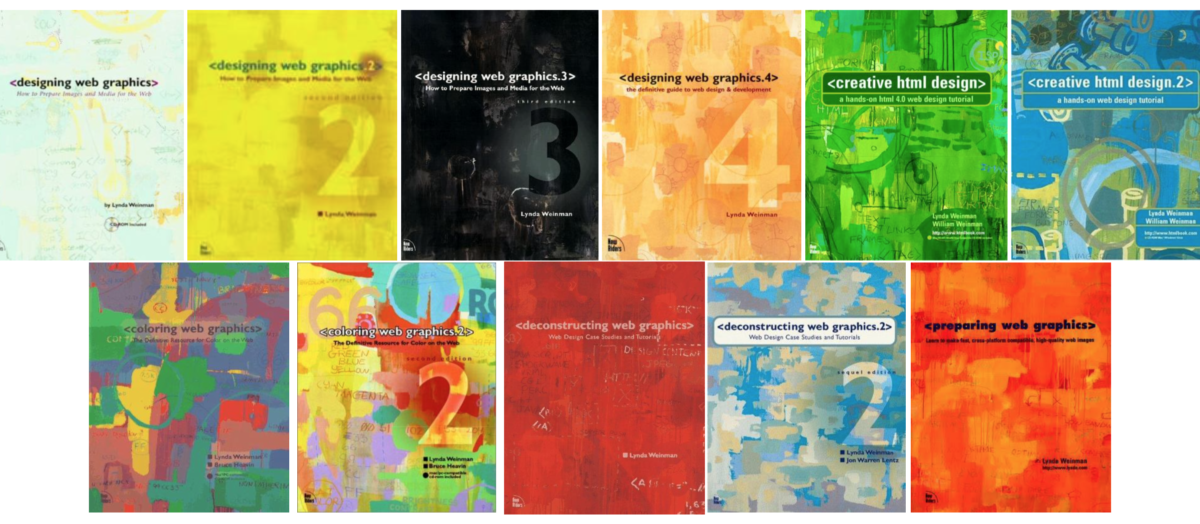

Lynda WeinmanProject type

Irina BlokProject type

Jane Fulton SuriProject type

Carolina Cruz-NeiraProject type

Lucy SuchmanProject type

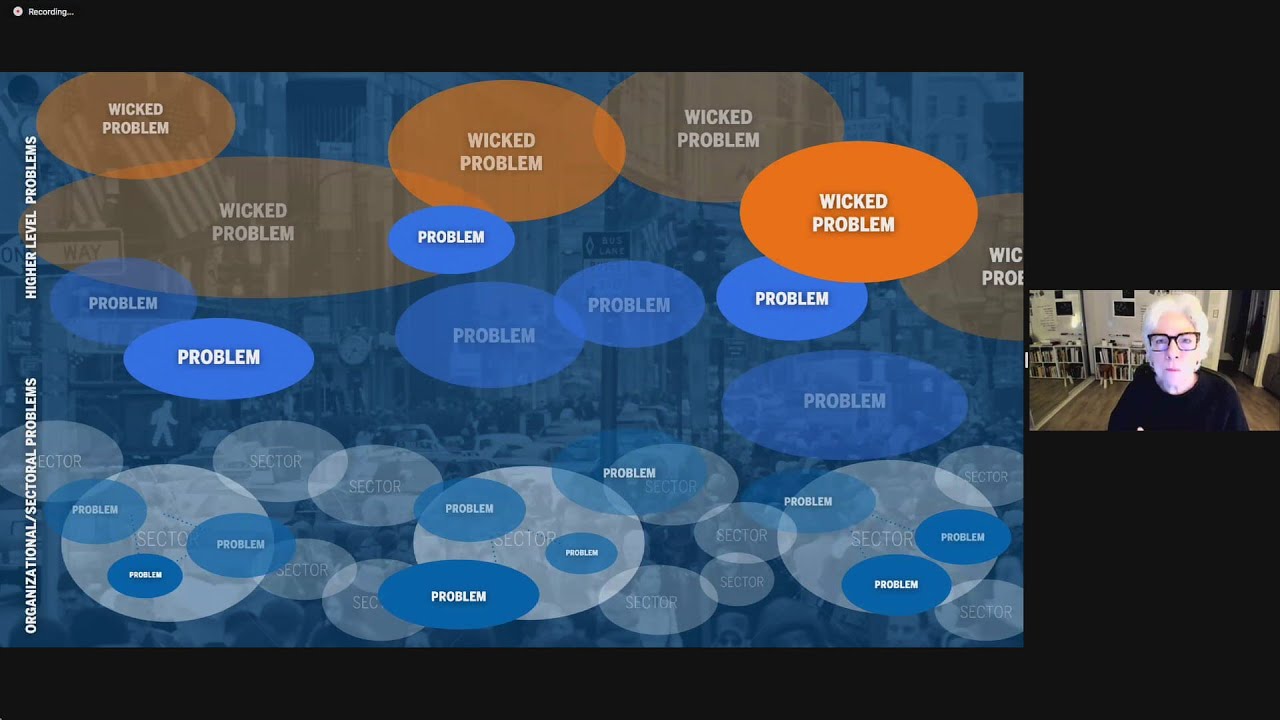

Terry IrwinProject type

Donella MeadowsProject type

Maureen StoneProject type

Ray EamesProject type

Lillian GilbrethProject type

Mabel AddisProject type

Ángela Ruiz RoblesDesigner