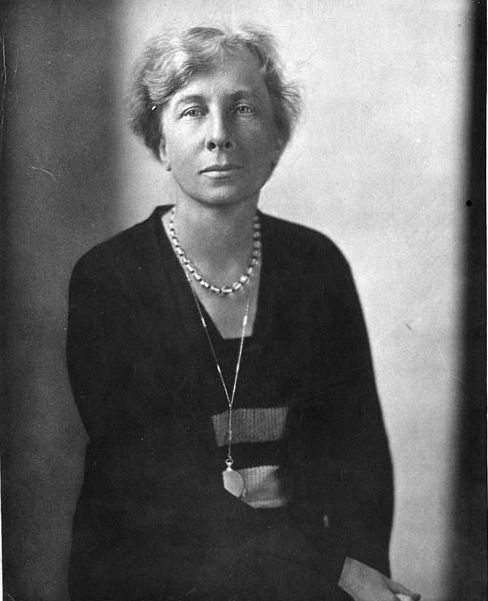

Lillian Gilbreth

Written by Erin Malone

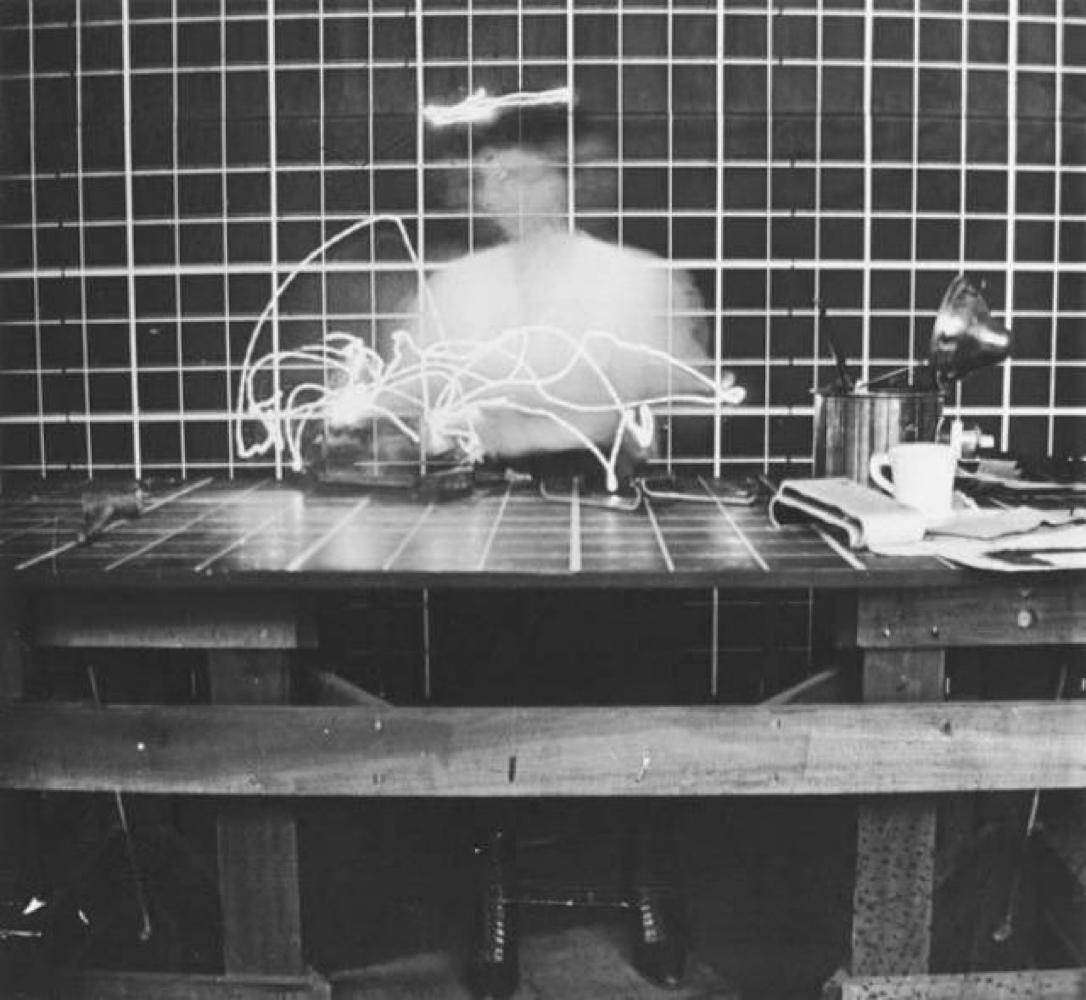

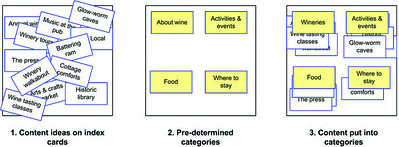

Lillian Gilbreth, along with her husband Frank, used the new technology of film in a series motion studies to watch workers in industrial factories do their work. They also studied WW1 soldiers dismantle and reassemble guns, carefully watching their motions, then revising their movements and having them dismantle and reassemble in the dark to confirm efficiencies. These motion studies assessed the mechanics of their form and were used to revise both machines and processes for the most functional efficiencies and better human factors. Their work highly benefited corporations and in some cases workers by introducing more ergonomic processes.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth (1878-1972) earned a Ph.D. in psychology from Brown University but is best known, along with her husband Frank Bunker Gilbreth, for revolutionizing management techniques. Image from the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Stills from the films made by Frank and Lillian Gilbreth showing the motions of workers. They used these studies to help create more efficient work processes and motions.

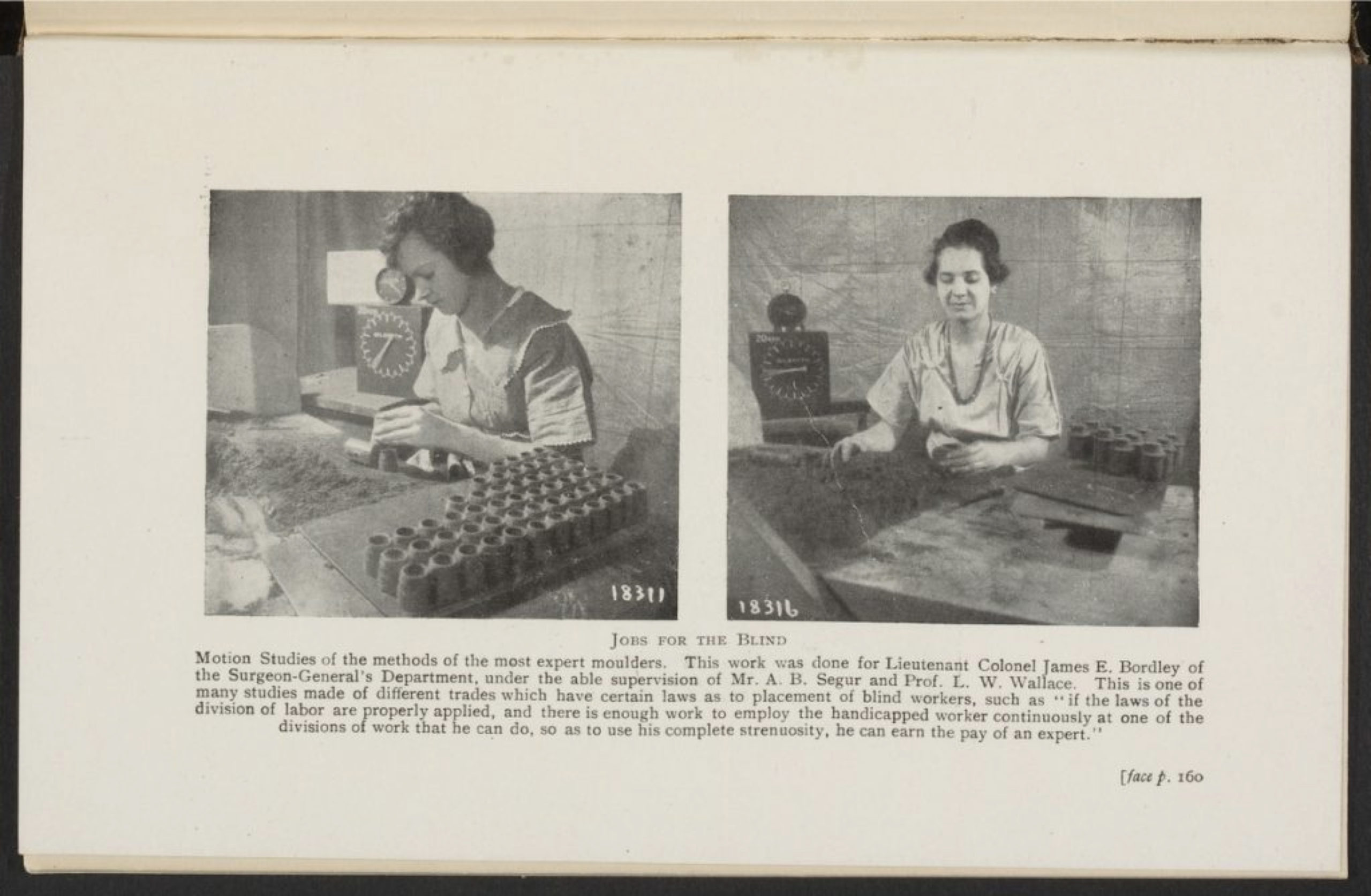

Motion studies of the methods of the most expert moulders. This work was done for Lieutenant Colonel James E. Bordley of the Surgeon-General's Department. This is one of the many studies made of different trades which have certain laws as to placement of blind workers.

When her husband died, Gilbreth continued working and after the war, she used her methods and research to design and create more efficient kitchens for handicapped women as well as for the growing number of middle-class and upper middle-class housewives needing to get more done without the benefit of household help.

Despite these efficiencies for labor, the underlying result was women moving into the role of servant to the household, thereby validating women’s roles as unpaid domestic labor.[1] Gilbreth’s work eventually focused on increasing customer satisfaction for all sorts of people, especially older, disabled people. Gilbreth worked well into her 80s, lectured annually, and supported her family through contract work. She was the first woman to receive honorary doctorate degrees from multiple universities.

Model kitchen for study in classes taught by Lillian Gilbreth. The efficiency work that she led had to do with innovations in technology and appliances to generally make women more efficient in the kitchen so they could do more. (without servants or help)

Lillian Gilbreth is considered the mother of industrial engineering, which helped create the practice of human factors engineering. Her work in human factors was done for corporations and in the service of capitalism yet the human factors improvements helped workers and soldiers and multiple generations of housewives and home cooks.

Footnotes:

[1] Shaowen Bardzell, “Feminist HCI,” Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’10, 2010, 1301–10, https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753521.

Bibliography:

To read more about the work of Lillian Gilbreth and her husband check out the following:

- Making Time: Lillian Moller Gilbreth -- A Life Beyond "Cheaper by the Dozen" by Jane Lancaster

- Cheaper by the Dozen by Frank B. Gilbreth and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey

- As I Remember: An Autobiography by Lillian M. Gilbreth

- Fatigue Study, the Elimination of Humanity's Greatest Unnecessary Waste, A First Step in Motion Study by Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Lillian Moller Gilbreth

- Applied Motion Study, A Collection of Papers on the Efficient Method to Industrial Preparedness by Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Lillian Moller Gilbreth

- The Psychology Of Management by Lillian Moller Gilbreth

Selected Stories

Ari MelencianoProject type

Mizuko Itoresearch

Boxes and ArrowsProject type

Mithula NaikCivic

Lili ChengProject type

Ovetta SampsonProject type

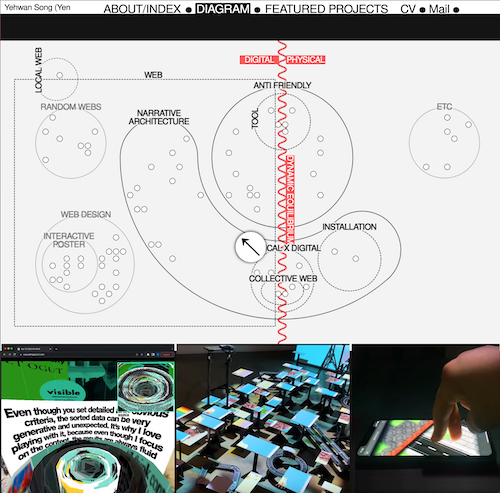

Yehwan SongProject type

Anicia PetersProject type

Simona MaschiProject type

Jennifer BoveProject type

Chelsea JohnsonProject type

Donna SpencerProject type

Lisa WelchmanProject type

Sandra GonzālesProject type

Amelie LamontProject type

Mitzi OkouProject type

The Failings of the AIGAProject type

Jenny Preece, Yvonne Rogers, & Helen SharpProject type

Colleen BushellProject type

Aliza Sherman & WebgrrrlsProject type

Cathy PearlProject type

Karen HoltzblattProject type

Sabrina DorsainvilProject type

Lynda WeinmanProject type

Irina BlokProject type

Jane Fulton SuriProject type

Carolina Cruz-NeiraProject type

Lucy SuchmanProject type

Terry IrwinProject type

Donella MeadowsProject type

Maureen StoneProject type

Ray EamesProject type

Lillian GilbrethProject type

Mabel AddisProject type

Ángela Ruiz RoblesDesigner